I considered writing this week’s blog about President Trump’s declaration of a national emergency, or which Democrat jumped into the presidential race most recently, or AOC’s latest crackpot proposal, but decided instead to write about Ulysses S. Grant. Yes, Ulysses S. Grant.

First of all, when I began writing the blog on Monday, it was Presidents Day and Grant was, after all, one of our Presidents (specifically our 18th.) But more significantly, I attended a dinner last week in the Library of Congress’s Jefferson Building, followed up by a visit to the Library of Congress’s Madison Building the next day, which I thought you might find interesting.

The speaker for the evening was Ronald Chernow, who among other things authored the book Alexander Hamilton. This book was adapted into the hit Broadway musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda, which of course is currently being performed at the Aronoff here in Cincinnati.

However, I’d like to focus my attention this week on another key American figure he wrote about (who hasn’t yet become the subject of a Broadway musical), Ulysses S. Grant. The Chernow book on Grant came out in October, 2017. I tend to be pretty tight with money (both the taxpayers’ and my own) so I seldom buy books, preferring to get them from either the local library in Cincinnati, or from the Library of Congress in D.C. The Grant book must have been in pretty high demand, because it took quite a while to get it. To my surprise, the book that was finally dropped off at my office turned out to be the LARGE PRINT edition, so I lugged this 1,600-page book around for about a month that must have weighed 30 pounds. But it was worth it – a great read.

Ironically, about a week after I finished it, I was the guest speaker for a group called the Ripon Society in Washington (this public policy organization takes its name from Ripon, Wisconsin, where the Republican Party was founded back in 1854.) After my speech, they presented me with a token of their appreciation – a copy of the Grant book. I didn’t have the heart to tell them I’d just read it, so I thanked them politely, accepted the book, and sat down.

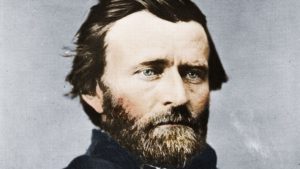

Anyway, back to Chernow and Grant. It was a fascinating discussion of Ulysses S. Grant’s rise from obscurity (selling firewood on the street corner in St. Louis), to commander of the Union Forces in the Civil War, to President of the United States. Grant’s drinking was explored – yes, he was a binge drinker, who would drink heavily for a couple of days, but then not drink a drop for months at a time, and never before or during a significant military engagement. It was said that his initials, U.S., could appropriately stand for “unconditional surrender” yet he personally granted (no pun intended) very generous terms of surrender to General Lee and his Confederate troops at Appomattox Courthouse.

After prevailing in the Civil War, Grant was later of course elected President of the United States, and whereas he has traditionally been viewed by historians as a failure in that position (for a long time being ranked at or near the bottom, with Harding and Nixon), he has been steadily rising in recent years. His two administrations were rife with corruption, but he himself was virtually the epitome of honesty. Unfortunately, he trusted people with an almost childlike naivety, and the wrong people took advantage of his faith in them time and time again.

After Grant left the presidency, he was swindled out of his family fortune by an unscrupulous business partner. In order to provide for his wife and children after his death, he decided to write his memoirs. Dying of throat cancer (he was a heavy cigar smoker for years) he sat day after day on his front porch in great pain writing his autobiography in his own hand.

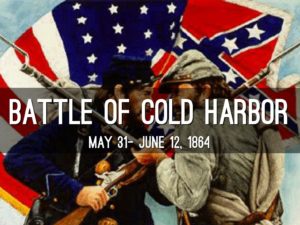

Chernow mentioned that in doing the research for his book, he’d spent time in the archives of the Library of Congress viewing Grant’s handwritten notes. I thought it would be incredibly interesting to view those notes myself, so I made arrangements to visit the Library of Congress the next day. Seeing Grant’s recollection of the Civil War and what he was thinking at the time expressed in his own handwriting was quite a moving experience. One thing particularly poignant to me was related to the Battle of Cold Harbor, which took place just outside Richmond, Virginia in 1864. Concerning the battle, Grant wrote, “I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made. No advantage was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained.” My great-great-grandfather on my mother’s side was killed during that battle.

Ulysses S. Grant died just three days after he finished writing his memoirs. They were a great success. The memoirs sold exceedingly well, and ensured that his wife and family were provided for after his passing, just as he had intended. His publisher was none other than Mark Twain, who called Grant’s autobiography “the best memoirs of any general’s since Julius Caesar’s.”

Some have speculated that Grant’s memoirs were so well written that he didn’t actually write them; that Mark Twain had. However, since Grant painstakingly wrote them out by hand himself, and they matched up with countless military orders he’d prepared during the war, we know Grant did indeed author his own memoirs. And they have undoubtedly withstood the test of time.